Tolstoy Tried to Kill My Girlfriend features several famous writers as characters – here’s a quick introduction to the key figures, and why they’re important.

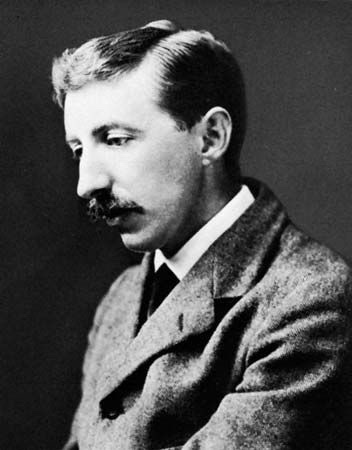

E. M. Forster (1879 – 1970)

Forster doesn’t physically appear in this play, but he does haunt it. It was Forster who was my initial inspiration for the writer Deacon, although, much like Heath, Deacon turned out to be a character who grew away from my initial intention!

Forster was part of the Bloomsbury group, a friend of Virginia Woolf, and author of such famous titles as Howard’s End, A Passage to India, and Where Angels Fear to Tread as well as early sci-fi story The Machine Stops.

That Forster was gay was known within his immediate circle, though not public. He lived through the infamous Oscar Wilde indecency trials of 1895 in which Wilde was prosecuted for homosexuality and sentenced to prison time, as well as through the 1969 Stonewall riots, thus witnessing a huge change in fight for queer rights.

In later years, Forster was a close friend and mentor to Christopher Isherwood (author of Goodbye to Berlin), but despite the greater leniency of the 1960s, he was still not publicly out. Upon his death he bequeathed a novel to Isherwood.

That novel was Maurice, a story about a young gay man at the start of the twentieth century: Maurice goes to a doctor thinking something is wrong with him, and asks to be cured. Gradually he comes to terms with his sexuality, falls in love, and has his heart broken, falls in love again. The ending of the novel (and SPOILER ALERT, obviously) sees Maurice retire to the country with his second love, and live a quiet and happy life with him, away from society.

When I first read this book I cried at the end; I’d expected misery for Maurice, but somehow this vision of happiness was all the more painful it was something he knew he would never be able to share.

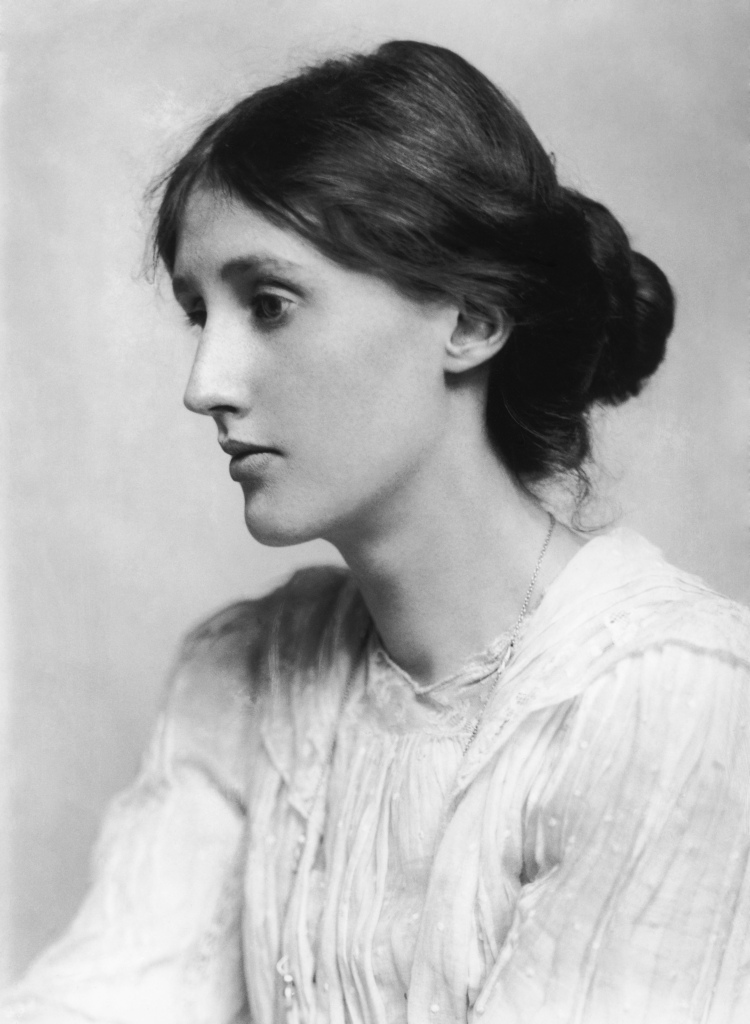

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf is something of a queer icon. Her love affair with Vita Sackville-West is well known (and if you haven’t read their letters, I strongly recommend you treat yourself – what a love affair!). Her novel Orlando is so far ahead of it’s time in its deconstruction of the gender binary. Orlando simply abandons one gender for another as they feel like it, and has male and female lovers, and sometimes lovers who dress female to earn their love and then reveal themselves to be male. It’s a peculiar novel that masquerades as a biography, and has plenty of witty observations that smash conventional ideas of gender and other societal norms.

I loved writing Virginia. I found her a playful character, immensely curious, and somewhat playful. Her real-life relationship with Forster really helped me to shape her attitudes to Deacon. Woolf and Forster often talked frankly about love and sex, even though Forster, for all his own homosexuality, wasn’t too sure about lesbians (oh dear).

In the play she is often watching people, bickering with Tolstoy, and generously encouraging others to find their voice and their purpose.

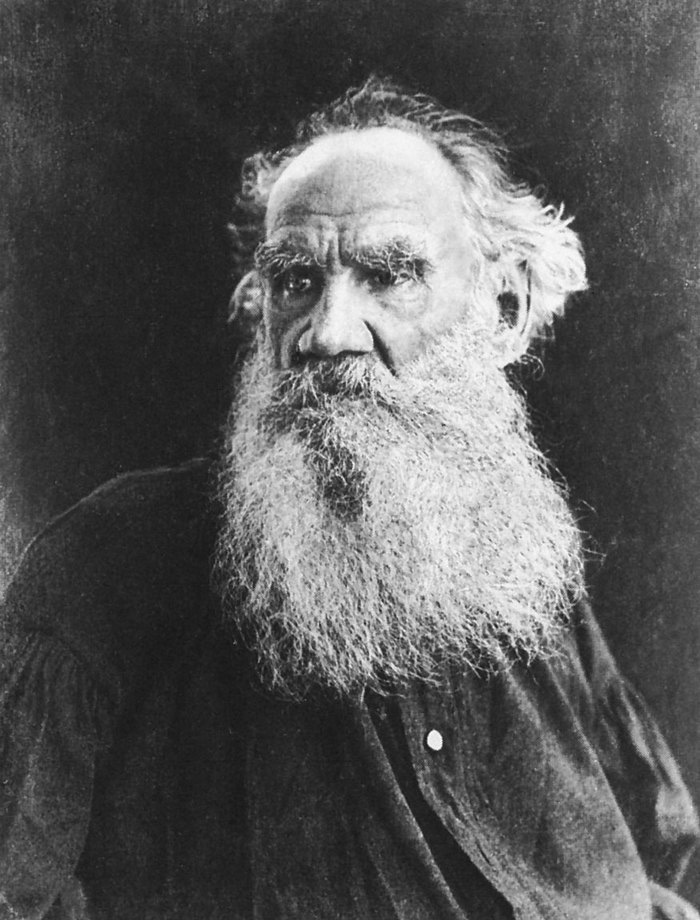

Lev Tolstoy

Of course, I’ve got to talk about Tolstoy! He gets into the title after all.

Tolstoy is obviously a central figure of the play, but this is perhaps surprising. He represents the cannon and the status quo that so many queer writers like Deacon feel the need to conform to. While many readers find his moral writings difficult to read and even harder to follow, absolutely no one can doubt his genius as a writer. War and Peace and Anna Karenina are utterly fabulous explorations of humanity.

In the play we explore the contradictions between what Tolstoy set out to do, and what he ultimately ended up doing. When I was doing my MA in Russian Literature at UCL I was fascinated by how Tolstoy’s ideas started out as one thing (writing Anna Karenina to show how a silly society woman cheating on her husband affected that noble long-suffering husband), and ended up another (a sensitive portrayal of a woman in an impossible situation, trapped in a loveless marriage, doing what is clearly right for her, but tormented by society’s response). One of my favourite scenes in the play occurs in act two, when after much of Tolstoy’s moralising, Anna Karenina herself sweeps in and confronts him.

I reread Anna Karenina for this, and was struck by the addition of the character Levin (who many see as a Tolstoy himself -Lev/Levin anyone?) who at first condemns Anna’s actions, but slowly comes round to understanding her by the time they finally meet. I suspect this novel ended up being about Tolstoy himself coming to understand a woman like Anna.